October - December 2006 Vol 2 Issue 11

The term ‘green marketing’ has been defined differently in different forums. A fairly comprehensive definition is provided below:

“Green or environmental marketing consists of all activities designed to generate and facilitate any exchanges intended to satisfy human needs or wants, such that the satisfaction of those needs and wants occurs, with minimal detrimental impact on the natural environment.” (Polonsky 1994).

The above definition, as its author points out, underscores the realization that the process of meeting human needs and wants is bound to harm the natural environment to a certain extent. It would thus be more apt to term green products, processes and systems as being less or more detrimental to the environment, rather than using the terms ‘environmentally friendly’ or ‘environmentally safe’.

A commonly accepted view of green marketing is that of the advertising or promotion of a product as being more environmentally friendly. However, it must be mentioned that such claims have to be backed by actual environmentally positive initiatives to be included in the category of green marketing. In fact, a number of countries have introduced ecomark schemes to help firms authenticate their green claims. .

NEED FOR A HOLISTIC APPROACH

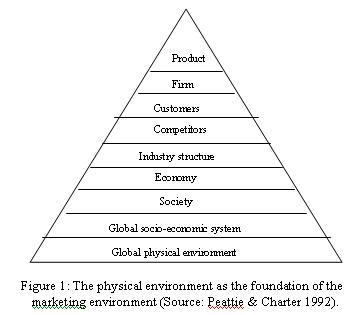

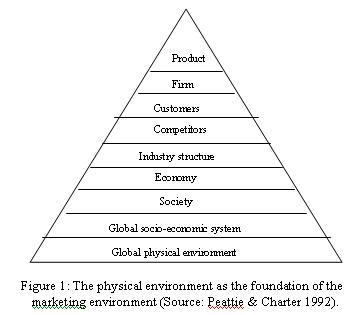

According to Capra (1983), traditional marketing theory has not taken into consideration the import of the ecological facets of the environment in which economic activity takes place. While substantial attention has been paid to social, cultural, political, and legal environments, the physical environment issues are often treated as a response to political or social pressures. Instead, the marketing environment should be envisaged as consisting of “layers of issues and interactions, with the physical environment as the foundation on which societies and economies are based” (Peattie and Charter 1992). Although many businesses may not consider environmental problems and issues to be of immediate relevance, but the truth is that business is very much dependent upon the physical environment. in which it exists (refer figure 1)

Figure 1: The physical environment as the foundation of the

marketing environment (Source: Peattie & Charter 1992).

WHY IS BUSINESS EMBRACING THE GREEN CONCEPT?

Based on a review of the literature on the subject Polonsky (1994) has identified several possible reasons for companies adopting green marketing.

Green Makes Business Sense

Green marketing is viewed as a means to achieve the organization’s objectives (Keller 1987, Shearer 1990). Several studies indicate that consumers and the general public were concerned about the environment (Roberts 1995, Roberts and Bacon 1997, Van Liere and Dunlop 1981, McCarty and Shrum 1994). Studies also indicate that concern for the environment is being reflected in changes in consumption-related perceptions and behaviour (Allen and Ferrand 1999, Gamba and Oskamp 1994, Shrum et al 1995). Phillips (1999) reported that 87 % of U.S. adults are concerned about the natural environment and 59 % of them say that they look for environmental labels and choose the brands that are more environmental-friendly.

Closer home, in a comprehensive attitudinal and behavioral analysis of Indian consumers as regards green marketing, Jain and Kaur (2004), found that Indian consumers surveyed report a high level of concern for the environment and engagement in environmental behavior. “On a personal level, respondents positively affirm that they have been influenced by green communication campaigns. They exhibit willingness to take environmentally friendly actions, seek environment-related information, and pursue activities that help conserve the environment and prevent pollution” (Jain and Kaur, 2004).

If consumers will prefer brands that they identify as being more environmentally safe to brands which they see as being less so, then it seems only reasonable for firms to position their products in the former category. Greening is thus viewed as a source of competitive advantage. ITC’s Bhadrachalam paper unit has invested in a Rs. 500 crore technology that makes the unit chlorine free. The benefit of being an elemental chlorine free (EFC) unit is that it is able to produce food-grade paper that can claim compliance with EU and US norms. Amway claims that its products are environmentally friendly.

The high cost of disposal of waste may cause businesses to re-examine their inputs and production processes. This may lead to use of more environmentally friendly raw material or the introduction of more efficient or green technology, resulting in cost-savings for the company. They may also look for buyers for their waste or by-products. The search for cost-savings may lead companies to develop ways of recycling their waste or by-products either for their own use or to be sold to other industries. Maruti Limited saved Rs. 26 Crores in the first year after obtaining an ISO 14001 certification. At Jubilant Organosys’s Distillery at Gajraula, the treated wastewater is piped to farmers and CO2 is sold to cola majors.

Green is the Color of Social Responsibility

Firms may also view greening as part of their moral obligation toward the local community and the larger society in which they exist. Thus, just as it is the obligation of organizations to ensure that they do not unfairly exploit human resources, similarly it is their obligation to ensure that they do not unfairly exploit the physical environmental resources. Thus, environmental responsibility is a part of their commitment to society. Polonsky (1994) points out the instances of companies such as Walt Disney World, which have instituted environmentally responsible behavior in their processes and systems, but do not promote the fact externally.

Green as a Result of Governmental and International Pressure

In many countries the government has introduced legislation aimed at forcing organizations to conduct their operations in a more environmentally responsible manner. This legislation is usually aimed at reducing production of harmful goods or by-products, reducing consumer and industry use of harmful products, and making it possible for consumers to evaluate the environmental impact of products (Polonsky 1994). In India, too a series of legislation has been enacted in order to reduce pollution of water, air and other environmental resources. Thus, the refrigerator industry has shifted from chloroflurocarbon (CFC) gases to more environmentally friendly gases. Table 1 lists various environmental regulations in force in India.

There are several international agreements, which require nations to adhere to specified environmental standards. For example, under the Montreal Protocol, nations are committed to protecting the ozone layer by controlling the release of chloroflurocarbons and halons. The Kyoto Protocol requires developed nations to reduce emission of greenhouse gas and outlines an agenda with regard to climate change. Similarly, the Basel Convention provides guidelines regarding the generation, transportation, and disposal of hazardous waste across nations.

Green as a Response to Competitor Initiatives

According to Polonsky (1994), at times firms may be forced to become more environmentally responsible because their competitors are taking major initiatives in that direction and using the fact as a marketing platform. In the context of the electricity industry in the U.S.A., Rader (1997) emphasized that it was not possible to have an effective green market unless and until there was a truly competitive market.

PATHS TO GREENNESS

Prakash (2001) has classified the different ways in which businesses can move towards greenness. According to him, green initiatives include changes in the value addition processes, changes in the management systems and changes in the products or modification of inputs. Changes in the value addition processes would include introduction of new technology for production, or modification of existing methods of production to reduce their environmental impact. Firms can also establish and ensure implementation of management systems designed to promote environmental, health and safety norms. Thus, Atlas Copco in India claims to use safer compressor condensate disposal practices including a step that removes oil from the water that is discharged into rivers.

Interventions at the product level could include the use of more environmentally safe raw material and other product inputs. McDonald has replaced its styrofoam containers with cardboard boxes. The U.K.-base Body Shop manufactures and sells natural ingredient-based cosmetics in recyclable packing. Proctor and Gamble has introduced refills for its cleaners and detergents in Europe that comes in throwaway packs. Kirloskar Copeland Limited (KLC) claims to have recently introduced the eco-friendly R404A gas compressor, which is used to run cold rooms, environmental chambers etc. KLC also offers natural fluids as refrigerants. According to Charter (1992) several other green measures are possible at the product level. These include product repair or product reconditioning to extend its life, designing the product so that it can be used several times, recycling the product so that it can be used as raw-material, or reducing the product such that it can offer the same benefits but use fewer raw materials or generate less waste. A campaign by Hindustan Levers Limited for its Surf Excel Quick Wash promotes the product as being able to save two buckets of water a day. Skoda in India promotes its cars as being 94 % recyclable.

OBSTACLES TO GREENNESS

There are however, several problems associated with organizations’ attempts to undertake green marketing practices. One major problem is that very often products that are more environmentally safe cost more. Though consumers say that they are willing to pay 7 to 20 % more for green products (Darymple and Parsons 2002), they not be willing to do this for expensive product-items or for products where the price differential between green and non-green brands is more.

Secondly, consumers may not like the performance or quality of green products. For example, ‘green’ tissue paper may not be as soft as its traditional counterpart. Thirdly, if firms make the packaging of their brands smaller, they may be at a disadvantage because of the reduced visibility of their brands on retail shelves. In addition, smaller packaging may be perceived as reduced quantity and will present a smaller surface for promotional messages. However, the good news, as pointed out by Ottoman (2006), is that there has been considerable improvement in the quality of green products and the technologies used to produce them. In an increasing number of cases, the claim can be made that these products are actually superior to their traditional counterparts. Ottoman gives the example of the Marathon fluorescent light bulb from Philips, which costs $15 but saves $26 over its life span.

Another problem associated with green initiatives is with regard to the current level of scientific knowledge about the final impact of various actions. Thus, what may be seen as more environmentally friendly today may actually turn out to be more harmful in the long term. Using the green platform for marketing in these instances may sometimes end up with a backlash for the organization involved.

ECO-LABELING INITIATIVES

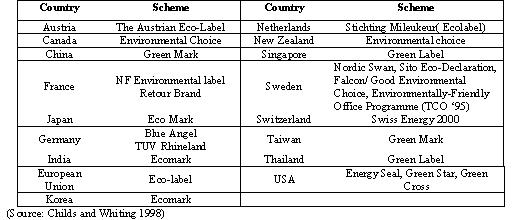

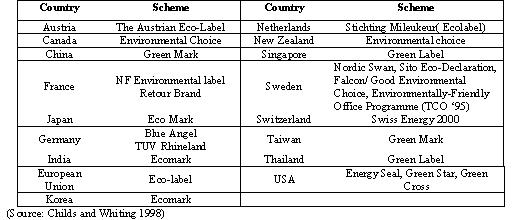

Eco-labels provide information regarding the environmental performance of products. Several countries have introduced eco-labeling initiatives. The objective of eco-labeling is to provide authentication to genuine claims regarding the environmental impact of products and processes by manufacturers. The eco-labeling schemes in several countries worldwide are given in Table 2.

In India, the government has introduced the Ecomark Scheme since 1981. The stated objectives of the scheme are:

(a) To provide incentives to manufacturers and importers to reduce adverse environmental impact of products.

(b) To reward genuine initiatives by companies to reduce adverse environmental impact of products.

(c) To assist consumers to become environmentally responsible in their daily lives by providing them information to take account of environmental factors in their daily lives.

(d) To encourage citizens to purchase products which have less environmental impact.

(e) Ultimately, to improve the quality of the environment and to encourage the sustainable management of resources.

The criteria followed for the Ecomark Scheme in India is founded on the ‘cradle to-grave approach’, that is, from the raw-material extraction to manufacturing and to disposal. To date, the final criteria for 16 product categories including soaps and detergents, paper, food items and packaging materials, has been declared.

CONCLUSION

Activist groups and the media have played a major role in enhancing the environmental awareness and consciousness of consumers in recent years. Most studies on the subject show that although the awareness and environmental behavior of consumers across countries, educational levels, age and income groups may differ, environmental concerns are increasing worldwide. Although their reasons for doing so may vary, businesses are responding to these concerns with an array of green marketing initiatives. For the organizations of the future, considerations about the long-term environmental impact of their actions will have to become an integral part of their business philosophy.

References

• Allen J.B. and Ferrand J. (1999), “Environmental Locus of Control, Sympathy and Pro-environmental Behaviour”, Environmenl and Behavior, 31(3): 338-53.

• Capra F. (1983), The Turning Point, Bantam.

• Charter M., (1992), Greener Marketing: a Responsible Approach to Business, Greenleaf: Sheffield.

• Childs C. and Whiting S., (1998), ‘Eco-Labeling and the Green Consumer,’ Working Paper from Sustainable Business Publications, Departmental of Environmental Sciences, University of Bradford, West Yorkshire.

• Coddington, W., 1993, Environmental Marketing and Strategies for Reaching the Green Consumer. McGraw Hill, New York.

• Dobhal , Shailesh, (2005) Business Today, May 8th,,p.22.v • Dalrymple D. J. and. Parsons L. J., Marketing Management: Text and Cases, 7th ed., John Wiley and Sons, 2002, 18-20.

• Fisk G., (1974), Marketing and Ecological Crisis, Harper and Row: London.

• Gamba R and Oskamp S. (1994), “Factors Influencing Community Residents Participation in Commingled Curbside Recycling Programmes”, Environment and Behaviour, 26(5): 587-612.

• Jain S. K. and Kaur G., (2004), ‘Green Marketing: An Attitudinal and Behavioral Analysis of Indian Consumers’, Global Business Review, Sage Publications, 5:2 187-205.

• Keller G.M., (1987, “Industry and the Environment: Towards a New Philosophy,” Vital Speeches, 54(50), 154-157

• Kotler, P. and Keller K. L., (2005), Marketing Management, 12th ed., Pearson Education • McCarthy J.A, and Shrum L.G., (1994), “The Recycling of Solid Waste: Personal Values, Values and Value Orientations and Attitudes about Recycling as Antecedents of Recycling Behaviour”, Journal of Business Research, 30(1): 43-62.

• Peattie K., (1992) Green Marketing, London: Pitman Publishing.

• Polonsky, Michael Jay (1994), ‘An Introduction to Green Marketing’. Electronic Green Journal at www.egj.lib.uidaho.edu.

• Philips L. E. (1999), “Green Attitudes”, American Demographics, 21; 46-47.

• Prakash, Aseem, (2002), “Green Marketing, Public Policy and Managerial Strategies”, Wiley InterScience , DOI: 10.1002/bse.338

• Rader, Nancy, (1997), “Fundamental Requirements for an Effective Green Market … And Some Open Questions” in Second Annual Conference on Green Pricing and Power Marketing.

• Roberts A. J. (1995), “Profiling Levels of Socially Responsible Consumer Behaviour: A Cluster Analysis Approach and it’s Implications for Marketing”, Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 3(4): 97-117.

• Roberts A. J. and Bacon D. R., (1997), “Exploring the Subtle Relationship Between Environmental Concern and Ecologically Conscious Consumer Behaviour”, Journal of Business Research, 40(1): 79-89.

• Shearer, J. W. 1990. "Business and the New Environmental Imperative." Business Quarterly 54 (3): 48-52.

• Shearer, Jeffery W. and Charles Futrell, (1987), Fundamentals of Marketing, 8th edition, New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

• Shrum L.J., McCarty J.A.and Lowery T. M., (1995), ‘Buyer Charecteristics of the Green Consumer and their Implications for Advertising Strategy’ Journal of Advertising, 24(2): 71-82.

Brainwave

Green Marketing: Drivers and Challenges

Meenakshi Handa

Faculty Member, University School of Management Studies

GGS Indraprastha University, Delhi

The term ‘green marketing’ has been defined differently in different forums. A fairly comprehensive definition is provided below:

“Green or environmental marketing consists of all activities designed to generate and facilitate any exchanges intended to satisfy human needs or wants, such that the satisfaction of those needs and wants occurs, with minimal detrimental impact on the natural environment.” (Polonsky 1994).

The above definition, as its author points out, underscores the realization that the process of meeting human needs and wants is bound to harm the natural environment to a certain extent. It would thus be more apt to term green products, processes and systems as being less or more detrimental to the environment, rather than using the terms ‘environmentally friendly’ or ‘environmentally safe’.

A commonly accepted view of green marketing is that of the advertising or promotion of a product as being more environmentally friendly. However, it must be mentioned that such claims have to be backed by actual environmentally positive initiatives to be included in the category of green marketing. In fact, a number of countries have introduced ecomark schemes to help firms authenticate their green claims. .

NEED FOR A HOLISTIC APPROACH

According to Capra (1983), traditional marketing theory has not taken into consideration the import of the ecological facets of the environment in which economic activity takes place. While substantial attention has been paid to social, cultural, political, and legal environments, the physical environment issues are often treated as a response to political or social pressures. Instead, the marketing environment should be envisaged as consisting of “layers of issues and interactions, with the physical environment as the foundation on which societies and economies are based” (Peattie and Charter 1992). Although many businesses may not consider environmental problems and issues to be of immediate relevance, but the truth is that business is very much dependent upon the physical environment. in which it exists (refer figure 1)

Figure 1: The physical environment as the foundation of the

marketing environment (Source: Peattie & Charter 1992).

WHY IS BUSINESS EMBRACING THE GREEN CONCEPT?

Based on a review of the literature on the subject Polonsky (1994) has identified several possible reasons for companies adopting green marketing.

Green Makes Business Sense

Green marketing is viewed as a means to achieve the organization’s objectives (Keller 1987, Shearer 1990). Several studies indicate that consumers and the general public were concerned about the environment (Roberts 1995, Roberts and Bacon 1997, Van Liere and Dunlop 1981, McCarty and Shrum 1994). Studies also indicate that concern for the environment is being reflected in changes in consumption-related perceptions and behaviour (Allen and Ferrand 1999, Gamba and Oskamp 1994, Shrum et al 1995). Phillips (1999) reported that 87 % of U.S. adults are concerned about the natural environment and 59 % of them say that they look for environmental labels and choose the brands that are more environmental-friendly.

Closer home, in a comprehensive attitudinal and behavioral analysis of Indian consumers as regards green marketing, Jain and Kaur (2004), found that Indian consumers surveyed report a high level of concern for the environment and engagement in environmental behavior. “On a personal level, respondents positively affirm that they have been influenced by green communication campaigns. They exhibit willingness to take environmentally friendly actions, seek environment-related information, and pursue activities that help conserve the environment and prevent pollution” (Jain and Kaur, 2004).

If consumers will prefer brands that they identify as being more environmentally safe to brands which they see as being less so, then it seems only reasonable for firms to position their products in the former category. Greening is thus viewed as a source of competitive advantage. ITC’s Bhadrachalam paper unit has invested in a Rs. 500 crore technology that makes the unit chlorine free. The benefit of being an elemental chlorine free (EFC) unit is that it is able to produce food-grade paper that can claim compliance with EU and US norms. Amway claims that its products are environmentally friendly.

The high cost of disposal of waste may cause businesses to re-examine their inputs and production processes. This may lead to use of more environmentally friendly raw material or the introduction of more efficient or green technology, resulting in cost-savings for the company. They may also look for buyers for their waste or by-products. The search for cost-savings may lead companies to develop ways of recycling their waste or by-products either for their own use or to be sold to other industries. Maruti Limited saved Rs. 26 Crores in the first year after obtaining an ISO 14001 certification. At Jubilant Organosys’s Distillery at Gajraula, the treated wastewater is piped to farmers and CO2 is sold to cola majors.

Green is the Color of Social Responsibility

Firms may also view greening as part of their moral obligation toward the local community and the larger society in which they exist. Thus, just as it is the obligation of organizations to ensure that they do not unfairly exploit human resources, similarly it is their obligation to ensure that they do not unfairly exploit the physical environmental resources. Thus, environmental responsibility is a part of their commitment to society. Polonsky (1994) points out the instances of companies such as Walt Disney World, which have instituted environmentally responsible behavior in their processes and systems, but do not promote the fact externally.

Green as a Result of Governmental and International Pressure

In many countries the government has introduced legislation aimed at forcing organizations to conduct their operations in a more environmentally responsible manner. This legislation is usually aimed at reducing production of harmful goods or by-products, reducing consumer and industry use of harmful products, and making it possible for consumers to evaluate the environmental impact of products (Polonsky 1994). In India, too a series of legislation has been enacted in order to reduce pollution of water, air and other environmental resources. Thus, the refrigerator industry has shifted from chloroflurocarbon (CFC) gases to more environmentally friendly gases. Table 1 lists various environmental regulations in force in India.

There are several international agreements, which require nations to adhere to specified environmental standards. For example, under the Montreal Protocol, nations are committed to protecting the ozone layer by controlling the release of chloroflurocarbons and halons. The Kyoto Protocol requires developed nations to reduce emission of greenhouse gas and outlines an agenda with regard to climate change. Similarly, the Basel Convention provides guidelines regarding the generation, transportation, and disposal of hazardous waste across nations.

Green as a Response to Competitor Initiatives

According to Polonsky (1994), at times firms may be forced to become more environmentally responsible because their competitors are taking major initiatives in that direction and using the fact as a marketing platform. In the context of the electricity industry in the U.S.A., Rader (1997) emphasized that it was not possible to have an effective green market unless and until there was a truly competitive market.

PATHS TO GREENNESS

Prakash (2001) has classified the different ways in which businesses can move towards greenness. According to him, green initiatives include changes in the value addition processes, changes in the management systems and changes in the products or modification of inputs. Changes in the value addition processes would include introduction of new technology for production, or modification of existing methods of production to reduce their environmental impact. Firms can also establish and ensure implementation of management systems designed to promote environmental, health and safety norms. Thus, Atlas Copco in India claims to use safer compressor condensate disposal practices including a step that removes oil from the water that is discharged into rivers.

Interventions at the product level could include the use of more environmentally safe raw material and other product inputs. McDonald has replaced its styrofoam containers with cardboard boxes. The U.K.-base Body Shop manufactures and sells natural ingredient-based cosmetics in recyclable packing. Proctor and Gamble has introduced refills for its cleaners and detergents in Europe that comes in throwaway packs. Kirloskar Copeland Limited (KLC) claims to have recently introduced the eco-friendly R404A gas compressor, which is used to run cold rooms, environmental chambers etc. KLC also offers natural fluids as refrigerants. According to Charter (1992) several other green measures are possible at the product level. These include product repair or product reconditioning to extend its life, designing the product so that it can be used several times, recycling the product so that it can be used as raw-material, or reducing the product such that it can offer the same benefits but use fewer raw materials or generate less waste. A campaign by Hindustan Levers Limited for its Surf Excel Quick Wash promotes the product as being able to save two buckets of water a day. Skoda in India promotes its cars as being 94 % recyclable.

OBSTACLES TO GREENNESS

There are however, several problems associated with organizations’ attempts to undertake green marketing practices. One major problem is that very often products that are more environmentally safe cost more. Though consumers say that they are willing to pay 7 to 20 % more for green products (Darymple and Parsons 2002), they not be willing to do this for expensive product-items or for products where the price differential between green and non-green brands is more.

Secondly, consumers may not like the performance or quality of green products. For example, ‘green’ tissue paper may not be as soft as its traditional counterpart. Thirdly, if firms make the packaging of their brands smaller, they may be at a disadvantage because of the reduced visibility of their brands on retail shelves. In addition, smaller packaging may be perceived as reduced quantity and will present a smaller surface for promotional messages. However, the good news, as pointed out by Ottoman (2006), is that there has been considerable improvement in the quality of green products and the technologies used to produce them. In an increasing number of cases, the claim can be made that these products are actually superior to their traditional counterparts. Ottoman gives the example of the Marathon fluorescent light bulb from Philips, which costs $15 but saves $26 over its life span.

Another problem associated with green initiatives is with regard to the current level of scientific knowledge about the final impact of various actions. Thus, what may be seen as more environmentally friendly today may actually turn out to be more harmful in the long term. Using the green platform for marketing in these instances may sometimes end up with a backlash for the organization involved.

ECO-LABELING INITIATIVES

Eco-labels provide information regarding the environmental performance of products. Several countries have introduced eco-labeling initiatives. The objective of eco-labeling is to provide authentication to genuine claims regarding the environmental impact of products and processes by manufacturers. The eco-labeling schemes in several countries worldwide are given in Table 2.

In India, the government has introduced the Ecomark Scheme since 1981. The stated objectives of the scheme are:

(a) To provide incentives to manufacturers and importers to reduce adverse environmental impact of products.

(b) To reward genuine initiatives by companies to reduce adverse environmental impact of products.

(c) To assist consumers to become environmentally responsible in their daily lives by providing them information to take account of environmental factors in their daily lives.

(d) To encourage citizens to purchase products which have less environmental impact.

(e) Ultimately, to improve the quality of the environment and to encourage the sustainable management of resources.

The criteria followed for the Ecomark Scheme in India is founded on the ‘cradle to-grave approach’, that is, from the raw-material extraction to manufacturing and to disposal. To date, the final criteria for 16 product categories including soaps and detergents, paper, food items and packaging materials, has been declared.

CONCLUSION

Activist groups and the media have played a major role in enhancing the environmental awareness and consciousness of consumers in recent years. Most studies on the subject show that although the awareness and environmental behavior of consumers across countries, educational levels, age and income groups may differ, environmental concerns are increasing worldwide. Although their reasons for doing so may vary, businesses are responding to these concerns with an array of green marketing initiatives. For the organizations of the future, considerations about the long-term environmental impact of their actions will have to become an integral part of their business philosophy.

References

• Allen J.B. and Ferrand J. (1999), “Environmental Locus of Control, Sympathy and Pro-environmental Behaviour”, Environmenl and Behavior, 31(3): 338-53.

• Capra F. (1983), The Turning Point, Bantam.

• Charter M., (1992), Greener Marketing: a Responsible Approach to Business, Greenleaf: Sheffield.

• Childs C. and Whiting S., (1998), ‘Eco-Labeling and the Green Consumer,’ Working Paper from Sustainable Business Publications, Departmental of Environmental Sciences, University of Bradford, West Yorkshire.

• Coddington, W., 1993, Environmental Marketing and Strategies for Reaching the Green Consumer. McGraw Hill, New York.

• Dobhal , Shailesh, (2005) Business Today, May 8th,,p.22.v • Dalrymple D. J. and. Parsons L. J., Marketing Management: Text and Cases, 7th ed., John Wiley and Sons, 2002, 18-20.

• Fisk G., (1974), Marketing and Ecological Crisis, Harper and Row: London.

• Gamba R and Oskamp S. (1994), “Factors Influencing Community Residents Participation in Commingled Curbside Recycling Programmes”, Environment and Behaviour, 26(5): 587-612.

• Jain S. K. and Kaur G., (2004), ‘Green Marketing: An Attitudinal and Behavioral Analysis of Indian Consumers’, Global Business Review, Sage Publications, 5:2 187-205.

• Keller G.M., (1987, “Industry and the Environment: Towards a New Philosophy,” Vital Speeches, 54(50), 154-157

• Kotler, P. and Keller K. L., (2005), Marketing Management, 12th ed., Pearson Education • McCarthy J.A, and Shrum L.G., (1994), “The Recycling of Solid Waste: Personal Values, Values and Value Orientations and Attitudes about Recycling as Antecedents of Recycling Behaviour”, Journal of Business Research, 30(1): 43-62.

• Peattie K., (1992) Green Marketing, London: Pitman Publishing.

• Polonsky, Michael Jay (1994), ‘An Introduction to Green Marketing’. Electronic Green Journal at www.egj.lib.uidaho.edu.

• Philips L. E. (1999), “Green Attitudes”, American Demographics, 21; 46-47.

• Prakash, Aseem, (2002), “Green Marketing, Public Policy and Managerial Strategies”, Wiley InterScience , DOI: 10.1002/bse.338

• Rader, Nancy, (1997), “Fundamental Requirements for an Effective Green Market … And Some Open Questions” in Second Annual Conference on Green Pricing and Power Marketing.

• Roberts A. J. (1995), “Profiling Levels of Socially Responsible Consumer Behaviour: A Cluster Analysis Approach and it’s Implications for Marketing”, Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 3(4): 97-117.

• Roberts A. J. and Bacon D. R., (1997), “Exploring the Subtle Relationship Between Environmental Concern and Ecologically Conscious Consumer Behaviour”, Journal of Business Research, 40(1): 79-89.

• Shearer, J. W. 1990. "Business and the New Environmental Imperative." Business Quarterly 54 (3): 48-52.

• Shearer, Jeffery W. and Charles Futrell, (1987), Fundamentals of Marketing, 8th edition, New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

• Shrum L.J., McCarty J.A.and Lowery T. M., (1995), ‘Buyer Charecteristics of the Green Consumer and their Implications for Advertising Strategy’ Journal of Advertising, 24(2): 71-82.