October - December 2006 Vol 2 Issue 11

Narratives are an important method of human-to-human communication. Combining the power of narrative with the flexibility of virtual environments (VEs) can create new and innovative opportunities in education, in entertainment, and in visualization.

INTRODUCTION

Storytelling is a significant method of human-to-human communication. We tell stories to share ideas, to convey emotions, and to educate. As new communication technologies have become available we have employed them in our storytelling, allowing us to reach wider audiences or to tell stories in new ways. Narratives were among the initial and most popular content types as books, radio, movies, and television were introduced to the public. VEs may provide the next technological advancement for presenting narratives. Consider the following examples.

Illustration 1

A child, nervous about an upcoming surgery, is given an opportunity to explore a virtual hospital. The child follows a patient about to undergo similar surgery, sees all the preparations that take place, and becomes familiar with the various people who are involved in the procedure. While he does not see the actual surgery take place, the environment makes sure the child notices that there are other children waiting for surgery and that they are all experiencing many of the same emotions that he is. He is reassured after his exploration — not just with his knowledge of the procedure, but that his fears and concerns are normal.

Illustration 2

A young adult begins interacting with a new mystery game set in a virtual environment. In the initial interactions, the player continually chooses to explore the environment and look for clues, rather than chase and subdue suspects. Noting the players interests, the game adjusts the plotline to emphasize puzzles rather than conflicts.

These examples illustrate three powerful, yet underutilized potentials of VEs. The first attribute is that events occur not randomly, but according to a plan based on scenario or narrative goals. The second attribute is that the system may recognize and respond to user goals and interests in addition to the given scenario goals. And the third attribute is that the system chooses when, where, and how to present events in order to best meet the user and scenario goals.

Narrative VE

Narrative VEs are an emerging multimedia technology, integrating storytelling techniques into VEs. VEs and virtual reality have been defined in different ways. For this section, we will define a VE as a computer-generated 3D space with which a user can interact. The concept of narrative also has different meanings in different contexts. A narrative is a sequence of events with a conflict and resolution structure (a story). So, for us, a narrative VE is an immersive, computer-generated 3D world in which sequences of events are presented in order to tell a story. Not all VEs are narrative, nor are VEs the only way of presenting computer-based narratives. Most VEs do not have an explicitly narrative structure. While most VEs include events of some sort, they do not provide the plot-driven selection and ordering of events that separates stories from simulation. For example, a driving simulator might model the roadways of a city, complete with cars, pedestrians, and traffic signals. Events in this simulation oriented VE might include a traffic light changing from green to red, a pedestrian successfully crossing an intersection, or a collision between two cars. In a simulation, the rules that govern when and how events occur are based primarily on attributes of the world and the object within it. In our driving VE, the stoplight may cycle from green to yellow to red every 30 seconds. Pedestrians cross roads successfully when there is no traffic. A collision may occur whenever the paths of two objects intersect at the same point in space and time. While simulation rules are adequate to describe object-object interactions and can even be used to model very complex environments (such as flying a 747 or driving through city traffic), they do not typically address broader goals or plans of the users or authors of the environment. The rules and random probabilities of a simulator do not take into account how an event will impact the environment or the user.

In a narrative VE, however, the occurrences of at least some key events are based on storytelling goals. For example, in a narrative VE designed to illustrate the dangers of jaywalking, the stoplight may turn green as soon as the user’s car approaches the intersection. The pedestrian may wait to start crossing the intersection until the user’s car enters the intersection. While these events may be similar to those in a simulator (traffic signal changes color, pedestrian crosses the street), the timing, placement, and representation of these events is done in such a manner as to communicate a particular story. This is what differentiates a simulation from a narrative.

Benefits of Narrative VE

Combining the power of narrative with the power of VEs creates a number of potential benefits. New ways of experiencing narratives as well as new types of VE applications may become possible. Existing VE applications may become more effective to run or more efficient to construct. Narrative VE can extend our traditional ideas of narrative. Unlike traditional narrative media, narrative VE can be dynamic, nonlinear, and interactive. The events in a narrative VE would be ultimately malleable, adapting themselves according to a user’s needs and desires, the author’s goals, or context and user interaction. A narrative VE might present a story in different ways based on a user profile that indicates whether the user prefers adventure or romance. A user could choose to view the same event from the viewpoint of different characters or reverse the flow of time and change decisions made by a character. A narrative VE might adapt events in order to enhance the entertainment, the education, or the communication provided by the environment. And a narrative VE might adapt events in order to maintain logical continuity and to preserve the suspension of disbelief. These narrative capabilities could also open up new application areas for VE. Training scenarios that engage the participant, provide incrementally greater challenges, and encourage new forms of collaboration could become possible. Interactive, immersive dramas could be created where the user becomes a participant in the story.

It is possible to add narrative elements to an otherwise simulation oriented VE, the process can be difficult for designers, and the results less than satisfying for users. The most common application area for simulation-oriented VEs with narrative elements is computer games. A review of the current state of the art in 3D narrative games is instructive in considering the challenges VE designers face.

Many computer games now include narrative elements, though the quality and integration of the narratives vary widely. One of the most common narrative elements is a Full Screen Video (FSV) cut-scene that advances the storyline. These typically take place after a player has completed a level or accomplished some other goal. Other devices include conversations with non-player characters (NPCs) that are communicated as actual speech, as text, or as a FSV. These conversations are typically scripted in advance, with the only interactivity coming from allowing the user to choose from prepared responses. Even with the best-produced narrative games, the narratives are generally tightly scripted and linear, providing little or no opportunity for influencing the plot of the story. Since the environment remains unaware of narrative goals, the designer must take measures to force users into viewing narrative events. This usually means either eliminating interactivity and forcing users to watch FSVs; or keeping interactivity, but eliminating choices so that the user must ultimately proceed down a particular path or choose a particular interaction. These solutions are unsatisfying for many users and time consuming for designers to construct.

A fundamental issue behind the limited interactivity is the tension between the user’s desire to freely explore and interact with the environment and the designer’s goals of having users experience particular educational, entertaining, or emotional events.

Advances in visualization technology have exacerbated the issue. VEs are now capable of modeling more objects, behaviors, and relationships than a user can readily view or comprehend. Techniques for automatically selecting which events or information to present and how to present it are not available, so VE designers must explicitly specify the time, location, and conditions under which events may occur. As a result, most VEs support mainly linear narratives or scenarios (if they support them at all).

Related Work

While there has been substantial research on the application of certain intelligent techniques to VEs, there has been little attention to adaptive interfaces for narrative VE. Still, in realizing architecture for adaptive narrative VE, many lessons can be drawn from work in related areas. These include adaptive interfaces, intelligent agents in VE, automated cinematography in VE, narrative multimedia, and narrative presentation in VE.

1. Adaptive interfaces are those that change based on the task, work context, or the needs of the user. Often, the successful application of an adaptive interface requires simultaneous development of a user modeling component. A user modeling system allows the computer to maintain knowledge about the user and to make inferences regarding their activities or goals. Adaptive interfaces allow computer applications to be more flexible, to deal with task and navigation complexity, and to deal with divers user characteristics and goals. Adaptive interfaces can be applied to almost any human/computer interaction. For example, the immense popularity of the WWW has lead to a corresponding amount of research on adaptive hypermedia.

2. Automated cinematography is a form of adaptivity particularly for VEs. Camera controllers or automated cinematographers are designed to free users and designers from explicitly specifying views. Simple camera controllers may follow a character at a fixed distance and angle, repositioning in order to avoid occluding objects or to compensate for user actions such as running. More complex controllers seek to model cinematography convention to dynamically generate optimal camera angles to support explicitly stated user viewing or task goals, or to link camera control to a model of the ongoing narrative.

AN ARCHITECTURE FOR NARRATIVE VE INTELLIGENT INTERFACE

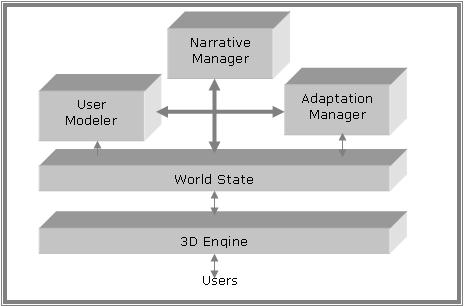

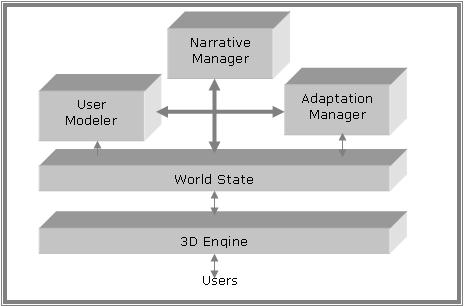

This architecture combines components common to adaptive systems and VE systems and adds data and control structures capable of representing and reasoning about narratives. The architecture includes the following components: Adaptation Manager, Narrative Manager, User Modeler, and a 3D Engine. While other VE systems devoted to narrative presentation have addressed elements of VE architecture, we believe that our approach to adapting events represents a unique contribution to the field. Our narrative VE architecture is illustrated in Figure.

I) 3D Engine

Graphic VEs rely on a 3D Engine to render the real-time images that make up the visual presentation of the environment. While there are many relevant research topics related to presentation of 3D images.

II) World State

The world state contains information about the object within the world, such as its location and its current status. This information may be maintained within the 3D engine or may be managed by an external data store.

III) User Modeler

User Modeling describes the ability of a system to make observations about a user and to use these observations to adapt the experience to better meet the user’s wants or needs. For a narrative VE system, the User Model could receive information such as a user profile, a history of user activities within the VE, and information about the activities of others with the VE. Using this information, the User Modeler could provide information regarding the user beliefs about the current story or which aspects of the story appear interesting to the user. The user model would also receive a record of activities performed by the user within the environment. This activity log would be more than just a list of specific interactions (e.g., movement to coordinates X, Y, Z, interaction with object Q, etc.), but would also provide contextual information used to establish the significance of interactions (e.g., moved farther away the threatening dog, interacted with the door to unlock the secret room, etc.). Using this information, the system could generate various “beliefs” about the user, such as the user’s goals (the user seeks recreation and intellectual stimulation), the users interests within the narrative VE (the user is seeking treasure and wealth), what the user believes about the narrative or the VE (the user believes that there is a treasure in the hidden room or the user believes that the dog is hostile and will attack), and whether the user falls into a recognized “type” (the user is an “explorer” rather than a “fighter”).

IV) Narrative Manager

In order to present a story, a VE requires some control mechanism for scheduling and presenting the events that make up the narrative. While simulation-oriented VE have rules for triggering or scheduling events, they do not take into account the narrative purpose of the events, instead focusing on some other guiding structure such as game physics. In the simplest narrative VEs (such as many recent computer games), narrative events are “canned” FSV pieces that occur when certain conditions are met, such as completion of a level, or the solution of a puzzle.

V) Adaptation Manager

Given an event and contextual information, the system should be capable of modifying the event to maintain plot and logical continuity and to help the user and author achieve their narrative goals. For the author, these goals may include communicating an idea, teaching a lesson, or conveying an emotion. For the user, goals might include entertainment, education, relaxation, or excitement. As input, the Adaptation Manager would use information from the Narrative Manager (narrative events), the User Modeler (user goals or beliefs), and the world state (object locations). Given a particular event suggested by the Narrative Manager, the Adaptation Manager will select time, place, and representation based on event constraints, narrative goals, and the state of the world.

CONCLUSION

The application of AI techniques in narrative generation and adaptation to multimedia technologies such as VEs can create new types of experiences for users. We have explored an architecture that supports not only the presentation of a single narrative, but an adaptive capability that would allow narratives to be customized for different users, different goals, and different situations.

by Himanshu Pandey, M.Tech.(Intelligent Systems), IIITA

Mansi Garg, M.Tech.(Intelligent Systems), IIITA

Technova

Adaptive Narrative Virtual Environments

Adaptive Narrative Virtual Environments

Narratives are an important method of human-to-human communication. Combining the power of narrative with the flexibility of virtual environments (VEs) can create new and innovative opportunities in education, in entertainment, and in visualization.

INTRODUCTION

Storytelling is a significant method of human-to-human communication. We tell stories to share ideas, to convey emotions, and to educate. As new communication technologies have become available we have employed them in our storytelling, allowing us to reach wider audiences or to tell stories in new ways. Narratives were among the initial and most popular content types as books, radio, movies, and television were introduced to the public. VEs may provide the next technological advancement for presenting narratives. Consider the following examples.

Illustration 1

A child, nervous about an upcoming surgery, is given an opportunity to explore a virtual hospital. The child follows a patient about to undergo similar surgery, sees all the preparations that take place, and becomes familiar with the various people who are involved in the procedure. While he does not see the actual surgery take place, the environment makes sure the child notices that there are other children waiting for surgery and that they are all experiencing many of the same emotions that he is. He is reassured after his exploration — not just with his knowledge of the procedure, but that his fears and concerns are normal.

Illustration 2

A young adult begins interacting with a new mystery game set in a virtual environment. In the initial interactions, the player continually chooses to explore the environment and look for clues, rather than chase and subdue suspects. Noting the players interests, the game adjusts the plotline to emphasize puzzles rather than conflicts.

These examples illustrate three powerful, yet underutilized potentials of VEs. The first attribute is that events occur not randomly, but according to a plan based on scenario or narrative goals. The second attribute is that the system may recognize and respond to user goals and interests in addition to the given scenario goals. And the third attribute is that the system chooses when, where, and how to present events in order to best meet the user and scenario goals.

Narrative VE

Narrative VEs are an emerging multimedia technology, integrating storytelling techniques into VEs. VEs and virtual reality have been defined in different ways. For this section, we will define a VE as a computer-generated 3D space with which a user can interact. The concept of narrative also has different meanings in different contexts. A narrative is a sequence of events with a conflict and resolution structure (a story). So, for us, a narrative VE is an immersive, computer-generated 3D world in which sequences of events are presented in order to tell a story. Not all VEs are narrative, nor are VEs the only way of presenting computer-based narratives. Most VEs do not have an explicitly narrative structure. While most VEs include events of some sort, they do not provide the plot-driven selection and ordering of events that separates stories from simulation. For example, a driving simulator might model the roadways of a city, complete with cars, pedestrians, and traffic signals. Events in this simulation oriented VE might include a traffic light changing from green to red, a pedestrian successfully crossing an intersection, or a collision between two cars. In a simulation, the rules that govern when and how events occur are based primarily on attributes of the world and the object within it. In our driving VE, the stoplight may cycle from green to yellow to red every 30 seconds. Pedestrians cross roads successfully when there is no traffic. A collision may occur whenever the paths of two objects intersect at the same point in space and time. While simulation rules are adequate to describe object-object interactions and can even be used to model very complex environments (such as flying a 747 or driving through city traffic), they do not typically address broader goals or plans of the users or authors of the environment. The rules and random probabilities of a simulator do not take into account how an event will impact the environment or the user.

In a narrative VE, however, the occurrences of at least some key events are based on storytelling goals. For example, in a narrative VE designed to illustrate the dangers of jaywalking, the stoplight may turn green as soon as the user’s car approaches the intersection. The pedestrian may wait to start crossing the intersection until the user’s car enters the intersection. While these events may be similar to those in a simulator (traffic signal changes color, pedestrian crosses the street), the timing, placement, and representation of these events is done in such a manner as to communicate a particular story. This is what differentiates a simulation from a narrative.

Benefits of Narrative VE

Combining the power of narrative with the power of VEs creates a number of potential benefits. New ways of experiencing narratives as well as new types of VE applications may become possible. Existing VE applications may become more effective to run or more efficient to construct. Narrative VE can extend our traditional ideas of narrative. Unlike traditional narrative media, narrative VE can be dynamic, nonlinear, and interactive. The events in a narrative VE would be ultimately malleable, adapting themselves according to a user’s needs and desires, the author’s goals, or context and user interaction. A narrative VE might present a story in different ways based on a user profile that indicates whether the user prefers adventure or romance. A user could choose to view the same event from the viewpoint of different characters or reverse the flow of time and change decisions made by a character. A narrative VE might adapt events in order to enhance the entertainment, the education, or the communication provided by the environment. And a narrative VE might adapt events in order to maintain logical continuity and to preserve the suspension of disbelief. These narrative capabilities could also open up new application areas for VE. Training scenarios that engage the participant, provide incrementally greater challenges, and encourage new forms of collaboration could become possible. Interactive, immersive dramas could be created where the user becomes a participant in the story.

It is possible to add narrative elements to an otherwise simulation oriented VE, the process can be difficult for designers, and the results less than satisfying for users. The most common application area for simulation-oriented VEs with narrative elements is computer games. A review of the current state of the art in 3D narrative games is instructive in considering the challenges VE designers face.

Many computer games now include narrative elements, though the quality and integration of the narratives vary widely. One of the most common narrative elements is a Full Screen Video (FSV) cut-scene that advances the storyline. These typically take place after a player has completed a level or accomplished some other goal. Other devices include conversations with non-player characters (NPCs) that are communicated as actual speech, as text, or as a FSV. These conversations are typically scripted in advance, with the only interactivity coming from allowing the user to choose from prepared responses. Even with the best-produced narrative games, the narratives are generally tightly scripted and linear, providing little or no opportunity for influencing the plot of the story. Since the environment remains unaware of narrative goals, the designer must take measures to force users into viewing narrative events. This usually means either eliminating interactivity and forcing users to watch FSVs; or keeping interactivity, but eliminating choices so that the user must ultimately proceed down a particular path or choose a particular interaction. These solutions are unsatisfying for many users and time consuming for designers to construct.

A fundamental issue behind the limited interactivity is the tension between the user’s desire to freely explore and interact with the environment and the designer’s goals of having users experience particular educational, entertaining, or emotional events.

Advances in visualization technology have exacerbated the issue. VEs are now capable of modeling more objects, behaviors, and relationships than a user can readily view or comprehend. Techniques for automatically selecting which events or information to present and how to present it are not available, so VE designers must explicitly specify the time, location, and conditions under which events may occur. As a result, most VEs support mainly linear narratives or scenarios (if they support them at all).

Related Work

While there has been substantial research on the application of certain intelligent techniques to VEs, there has been little attention to adaptive interfaces for narrative VE. Still, in realizing architecture for adaptive narrative VE, many lessons can be drawn from work in related areas. These include adaptive interfaces, intelligent agents in VE, automated cinematography in VE, narrative multimedia, and narrative presentation in VE.

1. Adaptive interfaces are those that change based on the task, work context, or the needs of the user. Often, the successful application of an adaptive interface requires simultaneous development of a user modeling component. A user modeling system allows the computer to maintain knowledge about the user and to make inferences regarding their activities or goals. Adaptive interfaces allow computer applications to be more flexible, to deal with task and navigation complexity, and to deal with divers user characteristics and goals. Adaptive interfaces can be applied to almost any human/computer interaction. For example, the immense popularity of the WWW has lead to a corresponding amount of research on adaptive hypermedia.

2. Automated cinematography is a form of adaptivity particularly for VEs. Camera controllers or automated cinematographers are designed to free users and designers from explicitly specifying views. Simple camera controllers may follow a character at a fixed distance and angle, repositioning in order to avoid occluding objects or to compensate for user actions such as running. More complex controllers seek to model cinematography convention to dynamically generate optimal camera angles to support explicitly stated user viewing or task goals, or to link camera control to a model of the ongoing narrative.

AN ARCHITECTURE FOR NARRATIVE VE INTELLIGENT INTERFACE

This architecture combines components common to adaptive systems and VE systems and adds data and control structures capable of representing and reasoning about narratives. The architecture includes the following components: Adaptation Manager, Narrative Manager, User Modeler, and a 3D Engine. While other VE systems devoted to narrative presentation have addressed elements of VE architecture, we believe that our approach to adapting events represents a unique contribution to the field. Our narrative VE architecture is illustrated in Figure.

I) 3D Engine

Graphic VEs rely on a 3D Engine to render the real-time images that make up the visual presentation of the environment. While there are many relevant research topics related to presentation of 3D images.

II) World State

The world state contains information about the object within the world, such as its location and its current status. This information may be maintained within the 3D engine or may be managed by an external data store.

III) User Modeler

User Modeling describes the ability of a system to make observations about a user and to use these observations to adapt the experience to better meet the user’s wants or needs. For a narrative VE system, the User Model could receive information such as a user profile, a history of user activities within the VE, and information about the activities of others with the VE. Using this information, the User Modeler could provide information regarding the user beliefs about the current story or which aspects of the story appear interesting to the user. The user model would also receive a record of activities performed by the user within the environment. This activity log would be more than just a list of specific interactions (e.g., movement to coordinates X, Y, Z, interaction with object Q, etc.), but would also provide contextual information used to establish the significance of interactions (e.g., moved farther away the threatening dog, interacted with the door to unlock the secret room, etc.). Using this information, the system could generate various “beliefs” about the user, such as the user’s goals (the user seeks recreation and intellectual stimulation), the users interests within the narrative VE (the user is seeking treasure and wealth), what the user believes about the narrative or the VE (the user believes that there is a treasure in the hidden room or the user believes that the dog is hostile and will attack), and whether the user falls into a recognized “type” (the user is an “explorer” rather than a “fighter”).

IV) Narrative Manager

In order to present a story, a VE requires some control mechanism for scheduling and presenting the events that make up the narrative. While simulation-oriented VE have rules for triggering or scheduling events, they do not take into account the narrative purpose of the events, instead focusing on some other guiding structure such as game physics. In the simplest narrative VEs (such as many recent computer games), narrative events are “canned” FSV pieces that occur when certain conditions are met, such as completion of a level, or the solution of a puzzle.

V) Adaptation Manager

Given an event and contextual information, the system should be capable of modifying the event to maintain plot and logical continuity and to help the user and author achieve their narrative goals. For the author, these goals may include communicating an idea, teaching a lesson, or conveying an emotion. For the user, goals might include entertainment, education, relaxation, or excitement. As input, the Adaptation Manager would use information from the Narrative Manager (narrative events), the User Modeler (user goals or beliefs), and the world state (object locations). Given a particular event suggested by the Narrative Manager, the Adaptation Manager will select time, place, and representation based on event constraints, narrative goals, and the state of the world.

CONCLUSION

The application of AI techniques in narrative generation and adaptation to multimedia technologies such as VEs can create new types of experiences for users. We have explored an architecture that supports not only the presentation of a single narrative, but an adaptive capability that would allow narratives to be customized for different users, different goals, and different situations.

by Himanshu Pandey, M.Tech.(Intelligent Systems), IIITA

Mansi Garg, M.Tech.(Intelligent Systems), IIITA